“His defence of bankers’ greed is Bullingdon morality, pure and simple.”

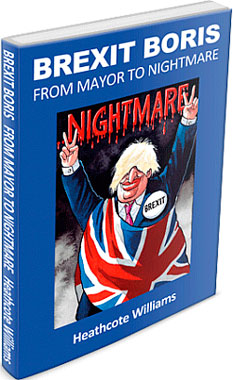

This is an extract from Brexit Boris: From Mayor to Nightmare, by the late and very much missed Heathcote Williams.

Boris Johnson’s penchant for violence would soon find a further outlet in the initiation rites of Oxford’s Bullingdon Club. Johnson was proud to be a member of the two hundred year old dining and drinking club and he would stand for its presidency. He was a keen participant in its excesses—raucous rituals described by an ex-member of it in the Guardian: “There’s the air of lurking violence, and above all the sense that its members consider themselves above the law on such occasions.”The club, whose youthful members like to dress up as if they belonged to a high-powered and gold-braided military elite, once enjoyed a “famously explosive dinner” at the White Hart near Oxford in 2005: “All the food and plates had been thrown everywhere and they were jumping on top of each other on the table like kids in a playground,” recalled the pub’s landlord Ian Rogers. The part he found strangest was that each time he confronted a member of the club, “they apologized profusely but offered absolutely no explanation”.

The Bullingdon Club is for plutocratic undergraduates who think nothing of spending £3,500 on its royal blue tailcoats with ivory lapels and canary yellow waistcoats—a livery which prompted Evelyn Waugh in Brideshead Revisited to describe the Bullingdon members as looking “like a lot of most disorderly footmen”.

The Bullingdon, described by Waugh in his novel Decline and Fall, published in 1928, as “baying for broken glass”, is still banned from meeting within a 15-mile radius of Christ Church. This stems from the time in 1927 when they smashed over 400 windows in the college’s Peckwater Quadrangle. In Waugh’s novel, the Bullingdon appears as the ‘Bollinger’, whose annual dinner was accompanied by “a confused roaring and a breaking of glass”.

Waugh says, in a description that is now almost a hundred years old but which still applies:

It is not accurate to call this an annual event, because quite often the club is suspended for some years after each meeting. There is tradition behind the Bollinger; it numbers reigning kings among its past members. At the last dinner, three years ago, a fox had been brought in in a cage and stoned to death with champagne bottles.

What an evening that had been! This was the first meeting since then, and from all over Europe old members had rallied for the occasion. For two days they had been pouring into Oxford: epileptic royalty from their villas of exile; uncouth peers from crumbling country seats; smooth young men of uncertain tastes from embassies and legations; illiterate lairds from wet granite hovels in the Highlands; ambitious young barristers and Conservative candidates torn from the London season and the indelicate advances of debutantes; all that was most sonorous of name and title was there for the beano.

The current Minister of Foreign Affairs in Poland, Radek Sikorski formerly of Pembroke College, was surprised to be woken up in the middle of the night in his lodgings in Oxford’s Walton Street and to be met by the sight of a marauding mob led by Boris Johnson, all whooping and chortling as Sikorski’s room was trashed and his possessions destroyed by a welter of cricket bats and cricket stumps wielded with sadistic glee.

Sikorski sat up in his bed, bemused. “In the middle of the night,” Sikorski recalls, “a dozen screaming figures burst into my room and demolished it completely.”

This was the Bullingdon Club’s thuggish way of telling someone that they’d just been made a member and that, having endured this introductory ritual without complaint, they would now be privileged to do the same thing to new members and to enjoy themselves in similar fashion at their expense: to shred their clothes; to rip their books in half; to hurl their hi-fi systems to the ground while wine bottles were emptied onto a pile of their belongings in the centre of the room and while photographs of their girl friends were ripped up and decried.

In a Guardian article titled ‘Young, rich and drunk’, Barney Ronay writes: “Then there’s the Bullingdon’s committed and longstanding misogyny. It’s not just the all-male exclusivity, more the tales of hiring strippers to preside at the initiation of new members at the annual breakfast. Plus the trapped, frantic and vaguely sexual energy of the whole thing. The Bullingdon is simply a no-go area for women. These are teenagers almost exclusively from an all-male boarding school background. It’s no real surprise that some of the naive, hostile and retarded attitudes fostered there resurface at a university reunion. You just have to hope they grow out of it.”

Another stock-in-trade of the Bullingdon initiation rituals was for newly elected members to visit Bonn Square where Oxford’s homeless congregate and to burn a £50 note in front of them by way of jeering at their misfortune.

The Club is most noteworthy for its trashing of the restaurants that it has booked for its antics and then for its members to assume that they can exonerate themselves by throwing banknotes at the hapless, and possibly ruined, proprietors. As Hilaire Belloc had it in his Cautionary Tales:

Like many of the Upper Class

He liked the sound of broken glass.

Belloc could well have been thinking of the members of the Bullingdon Club. At one Club meal in 1987, attended by both Boris Johnson and David Cameron, someone—whose identity has never been properly established thanks to the Bullingdon rule of omertà—threw a large plant pot through the restaurant window.

The burglar alarm was activated and Oxford’s police force duly descended on the dining club’s chosen venue with sniffer dogs in tow. Six of the group were apprehended and spent the night at Cowley police station.

Cameron escaped but Johnson’s attempt to evade the police by running off and crawling through a hedge in the Botanical Gardens failed and, by his own account, an overnight stay in a police cell reduced him to “a gibbering namby-pamby”.

Cameron seems sheepish about his Bullingdon past. When asked by the TV interviewer Andrew Marr whether he was embarrassed by it, the then Tory leader replied: “Of course, desperately, very embarrassed about it”. Johnson, however, seems proud of his Bullingdon membership and reputedly relishes hailing former members of the Club, so distinguished for its destructive binges, with a braying chant of “Buller! Buller! Buller!” which he expects to be reciprocated in a tribal bonding ritual.

Johnson’s defence of privilege is an enduring theme. In 1980, after extolling the virtues of private education he concluded: “So strain every nerve, parents of Britain, to send your son to this educational establishment (forget this socialist gibberish about the destruction of the State System). Exercise your freedom of choice because in this way you imbue your son with the most important thing, a sense of his own importance.”

The unfairness of the public schools’ leech-like presence within the country’s education system and their unwarranted charitable status—despite perpetuating an uncharitable class system—doesn’t faze Johnson for a moment.

He admires and he serves economic elitism. Eighty per cent of those who funded his campaign for the office of mayor of London were from the financial sector—hedge-funders, private equity experts, financial service houses and multi-millionaire businessmen—something that may have weighed with Johnson when he later attacked the top tax rate for high earners and with his regarding “banker bashers” as deluded.

In November 2013 Johnson said the super-wealthy were “a put upon minority”, and ludicrously described them as being “like Irish travellers and the homeless”. In the same year the super-wealthy were to bag an average 14 per cent pay rise while the average wage rose by a paltry below-inflation 0.7 per cent.

“Since his first months in office,” Sonia Purnell noted, “Boris’s attitude towards the City and the super-rich has been at odds with his ‘Mayor of the People’ persona. As Simon Jenkins of the Standard tellingly puts it: “His defence of bankers’ greed is Bullingdon morality, pure and simple.”

Johnson’s more acute sister Rachel, a novelist, has commented on an infamous Bullingdon Club photograph (now strictly injuncted against publication) that features both her brother and Cameron: “It looks what it is, elitist, arrogant, privileged and of an age that would have little resonance with people on low incomes who didn’t go to Eton.”

In the “overbearing arrogance embodied in these sub-Gainsborough postures—in the twittish clothing, the floppy hair and the almost luminous sense of false entitlement which radiate from these historic images” —it’s not hard to hazard a guess at their subsequent career paths.

Brexit Boris: From Mayor to Nightmare

Uncovered here are the lies, the sackings, the betrayals, the racist insults, the brush with criminality, that should have got Boris Johnson disbarred from ever being considered for high office.

Uncovered here are the lies, the sackings, the betrayals, the racist insults, the brush with criminality, that should have got Boris Johnson disbarred from ever being considered for high office.

Available from Public Reading Rooms:

Price: £8 post free

![]()